An Old Panic in New Clothes

Conversations about artificial intelligence (AI) in writing often sound like moral panics.

Everywhere you turn, someone is proposing a “compass,” a “framework,” or an “ethical grid” to dictate how much AI assistance is acceptable, or when disclosure is required. These guides present themselves as indispensable for a new technological era, but in truth they construct a false — and often naïve — narrative around problems that are neither novel nor real.

But do we need them? I argue no.

The problem with these frameworks is simple: they mistake the tool for the author. Yes, AI can generate text from a prompt, but that does not make it the writer. Authorship lies in intent, not in the mechanics of process.

Just as photography did not require a moral scoring system when Photoshop filters appeared, and musicians did not need disclosure grids when ProTools and Auto-Tune entered the studio, writers do not need a special rubric to govern whether they used Grammarly, ChatGPT, or Claude to reorganize their thoughts.

The question has never been which tools you used. The question is what you did with them. Authorship norms — plagiarism, fabrication, attribution — exist and cover the ethical boundaries of writing. AI does not change those boundaries.

Tools Don't Create Deception — People Do

To see why frameworks like The Ethical AI Writing Compass are unnecessary, it helps to look back at history. Deception in writing is as old as writing itself, and it has never required new technologies to make it possible.

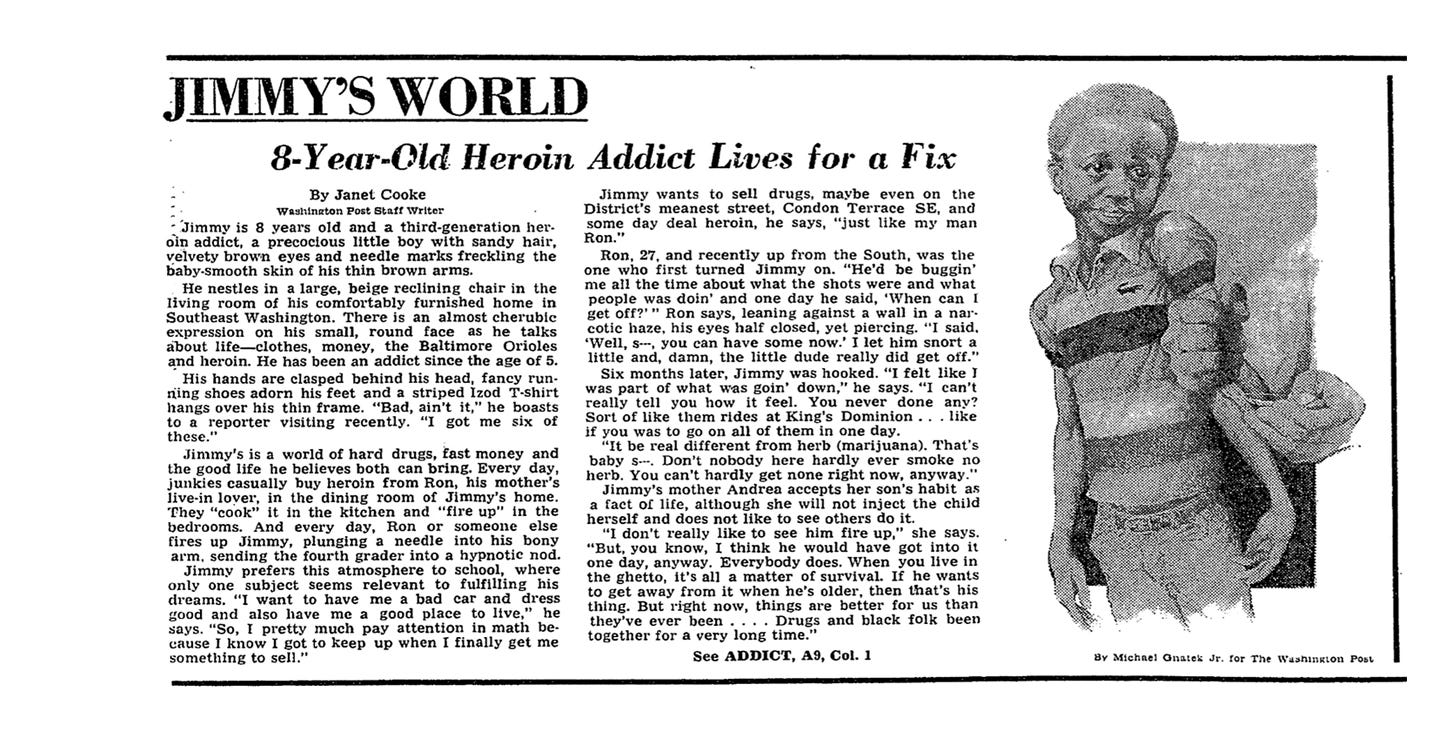

In September 1981, Janet Cooke of The Washington Post wrote “Jimmy’s World,” a harrowing feature about an 8-year-old heroin addict in Washington, D.C. The story won her the Pulitzer Prize — until it was revealed that “Jimmy” never existed. The entire article was fabricated.

Seventeen years later, Stephen Glass of The New Republic became a cautionary tale in American journalism. Glass fabricated sources, quotes, and even entire companies across more than two dozen articles. He built elaborate fake websites and phone numbers to dupe fact-checkers. His downfall came not through a moral framework, but through diligent editors and readers who noticed discrepancies.

In 2003, Jayson Blair at The New York Times plagiarized passages, invented datelines, and fabricated entire scenes. His deception was not uncovered by a compass of acceptable tool use; it was uncovered by editorial scrutiny and the unshakable standard that a reporter must tell the truth.

And in 2018, Claas Relotius at Der Spiegel — an award-winning German journalist — was exposed for inventing characters and storylines wholesale. His fabrications were so numerous that the magazine launched an internal investigation and retracted many of his features.

The pattern is clear. What unites Cooke, Glass, Blair, and Relotius is not the lack of a framework for their tools, but the deliberate choice to deceive. Long before AI, writers lied. Long before AI, plagiarism and fabrication shook institutions. What exposed these writers were not new ethical rubrics but the same standards that exist today: plagiarism policies, fact-checking, editorial oversight.

Context Already Provides Guardrails

Every domain already has its own norms of authorship:

Academia. Plagiarism is plagiarism, whether copied from a book, a classmate or ChatGPT. Student codes of conduct already make this clear.

Journalism. Fabrication, quote invention or ghostwriting without attribution are breaches regardless of whether the material comes from AI or a human assistant. Editorial standards prohibit this.

Literature. Ghostwriting has long been an accepted — if sometimes controversial — practice. No one demands an “ethical framework” to score how many sentences a ghostwriter contributed. Authors take responsibility for the published work, period.

Business writing. In internal memos, authorship is often irrelevant. Documents are collaborative by nature, and the goal is clarity, not personal expression. AI poses no unique ethical risk here.

By layering new frameworks on top of these existing norms, we risk redundancy at best and contradiction at worst. Students already have clear plagiarism policies. Journalists already have codes of conduct. Writers already own their words, regardless of tools. Why invent parallel rules that muddy the waters?

Ethical Anxiety Is a Cultural Reaction, Not a Technical Necessity

AI is not the first technology to spark panic about authenticity. Each wave of invention has carried its own cycle of suspicion before eventually settling into normalcy.

When photography emerged in the 1830s and 1840s, critics denounced it as mechanical. French poet Charles Baudelaire — one of the most influential literary figures of the 19th century — went so far as to call photography “art’s most mortal enemy.”

And when photographers began manipulating images through double exposure and retouching, critics worried that the medium’s truthfulness was compromised. In 1865, a famous portrait of Abraham Lincoln was created by pasting his head onto another politician’s body — an early “deepfake” scandal that sparked fears about photography’s integrity.

When typewriters spread in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, educators fretted over the loss of penmanship. Handwriting had long been seen as a mark of individuality and even moral character. Some critics argued the typewriter would encourage laziness in composition, making it too easy to dash off words without the discipline handwriting demanded.

In the 1980s, schools confronted the arrival of word processors. Some banned their use for student essays. A New York Times report in December 1983 (“School Computers: Help or Hindrance?”) described teachers who feared that “cut and paste” made writing too easy, undermining the discipline of composition. Today, the idea that word processors were once considered a threat to education seems absurd.

Each of these technologies was cast as ethically suspect. Each time, the panic faded. Each time, the tool became an invisible part of the creative process. AI is following the same trajectory. Today it is seen as a unique threat to authorship. Tomorrow it will be as mundane as spellcheck.

The Consequences of Over-Frameworking

The danger of AI frameworks is not that they prevent abuse — they don’t. The danger is that they create suspicion where none is warranted, both in how readers see writing and in how writers approach their craft.

External consequences: reader trust

If writers must disclose every AI interaction, trivialities risk being turned into scandals. Imagine a novelist confessing: “I used ChatGPT to suggest synonyms for ‘dark.’” Or a student disclosing: “I used Grammarly to check my commas.” By collapsing all tool use into one moral category, frameworks trivialize genuine violations —plagiarism, fabrication — while eroding trust in normal workflows.

Internal consequences: writer creativity

Bureaucratizing creativity is equally damaging. If every act of writing is scored, charted or quantified along an axis of “acceptable” AI use, writers will feel policed rather than empowered. Imagine novelists quantifying how many pages their editors rewrote or journalists logging every sentence suggested by a copy desk. Creativity thrives in ambiguity, not on grids. Overregulation would mean paralysis, not clarity.

Edge Cases: Where Transparency Matters

None of this is to say disclosure never matters. In edge cases, transparency is essential:

If you publish an investigative article, readers deserve to know if quotes were AI-generated.

If you submit a student paper, professors need to know whether the analysis is your own.

If you claim a memoir is raw personal truth, passing off AI-generated passages would be deceptive.

But these are not new ethical issues. They are the same ones we already face with ghostwriters, editors, fact-checkers and fabricators. The principle is simple: don’t lie about your authorship. That principle doesn’t need a new compass; it needs consistent enforcement of existing standards.

Conclusion: Back to Basics

Baudelaire worried that photography would create “an industry that could give us a result identical to Nature” and called it “the absolute of art.” His concern wasn’t really about cameras — it was about people mistaking mechanical reproduction for genuine creativity.

Today’s AI panic repeats that confusion. We are so focused on technical capability that we are missing what actually matters about writing.

We need the same things we’ve always needed: honesty about what is ours and what is borrowed, attribution where it is due and accountability for what we publish under our names. Everything else — how we got there, which tools we used, which drafts were aided by Grammarly, Claude or a thesaurus — is part of the messy, invisible process of writing.

To frame AI as uniquely dangerous is to forget that deception has always been a human problem, and that technological anxiety is a cultural reaction, not a technical necessity.

The frameworks we already have are sufficient. What we need is not more compasses, but more trust in the enduring principles of authorship: the writer owns the words, the writer owns the intent, and the writer owns the responsibility.